#BlackHistory #AfricanAmerican #Heroes #Inventors #GeorgeWashingtonCarver,#ClaudiaJones #BlackHistorymonth

In 1926, the US historian Carter G Woodson, the son of former slaves, launched Negro History Week to commemorate important people and events from the African diaspora. “If a race has no history,” he said, “it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.” Renamed and expanded in the 1970s, what we now know as Black History Month has been celebrated in the UK since 1987.

Q&A

What is Black History Month?

This year, as every year, the focus will be on pivotal and well-documented figures such as Martin Luther King, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. But there are others whose often radical work is frequently forgotten. In an effort to honour at least some of them, we asked black historians and cultural figures to nominate their own heroes and watershed events.

Robert Wedderburn by Kwame Kwei-Armah

Wedderburn was a 19th-century political firebrand, who was so powerful that he was put on a secret British government list of potentially dangerous reformers. He pushed for the end of slavery and the redistribution of wealth in Britain, publishing a book, The Horrors of Slavery, in 1824 and being arrested multiple times for his activism, which was considered “blasphemous”. He was controversial, but he was also part of a posse of people of colour who were all radical; not only defending themselves, but trying to uplift all marginalised people.

He was a real revolutionary, and I have no idea why he has been forgotten. People can learn from him today because he stood up to the government of the day in a form of radical rhetoric that challenged his environment. He spoke truth to power. He wanted the government to be egalitarian, and he wasn’t just looking out for black people. In today’s terms, we would call him intersectional, but he was doing that back then and focusing on people’s dignity, advocating for it from the pulpit and in print.

Kwame Kwei-Armah is the artistic director of the Young Vic

Emperor Septimius Severus by Olivette Otele

Septimius Severus, born in what is now Libya in 145, was the first black Roman emperor. His reign came after Marcus Aurelius, and he began what is seen as the last dynasty of the empire: the Severan dynasty. He was known for being a ruthless military leader, but is not well remembered, perhaps because of his race and because he has been overshadowed by flamboyant emperors such as Caesar and Nero.

There can be a dichotomy in black history – you are either the hero or the victim – yet here is someone who was immensely powerful and privileged, and an uncompromising man of his time.

When you think of the Roman empire, you never think of someone who was born in northern Africa, yet the empire was so vast that it sprawled beyond what we now call the west. There wasn’t as much of a rigid boundary between the continents then; that is a mere hierarchy we have since developed. Through Severus, we can see that those boundaries are artificial and that people of African descent held positions of great power throughout history.

Olivette Otele is a professor of history at Bath Spa University

Lewisham mothers against the sus law by Paul Boateng

There was a pivotal moment in my life, and in British life, in 1975 when a group of black mothers in Lewisham, south-east London, got together to campaign against the “sus” law that gave police the power to arrest anyone they suspected was loitering with intent to commit certain offences. This power was disproportionately used against young black men. One Tuesday night in February, these women came together and simply said “no”. They wanted to save their sons, and from that grew a whole movement.

I was a trainee lawyer at the time, and they came to me to ask for help. The campaign grew to involve churches and all the political parties and trade unions, until in 1980 it went before a home affairs select committee and it was finally recommended that the law be repealed.

It was a landmark for me in the history of black organisations in Britain. There is never any substitute for grassroots activism and organising. Power concedes nothing without a demand; it never has and it never will.

Paul Boateng is a Labour peer and former cabinet minister

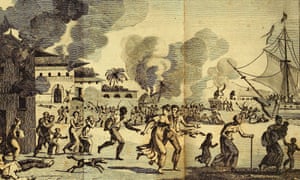

Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman by Kehinde Andrews

The Haitian revolution of 1791 to 1804 is the only successful slave rebellion in history. Part of the reason for its success is that it brought together all the enslaved people in the country. That was cemented through a Vodou ceremony on the night of 21 August 1791 at Bois Caïman, at which those present took an oath to take revenge on their French masters.

One of the things slavery did was to get rid of the African-ness of the enslaved – they would take away their names, and slaves weren’t allowed to mix with each other, speak their original language or keep their original religion. Many of the slaves in Haiti were African-born, so taking part in this ceremony, led by the high priest Dutty Boukman and priestess Cécile Fatiman, gave them licence to retain their traditions.

Vodou has its roots in the tribal religions of West Africa, and these slaves had brought them to Haiti to form the cultural practices of Vodou that we know today. It was empowering, and ultimately led them to revolt. Figures such as Toussaint L’Ouverture are remembered as the leaders, yet this grassroots African spirituality was equally important.

We now have a misguided aversion to Vodou, a concept that it is witchcraft, but this is the spiritual belief of an entire people, and it shouldn’t be denigrated. Being aware of your traditions and heritage is really important. It’s not witchcraft – it’s about connecting with African roots and keeping that alive.

Kehinde Andrews is a professor of black studies at Birmingham University

Claudia Jones by Valerie Amos

I grew up hearing a lot about Claudia Jones, who died in 1964 when I was 10. My parents would tell me how she had founded the Caribbean carnival, the precursor to Notting Hill carnival.

But that was not the important thing for me. Instead, it was that, throughout her political activism, first as a black feminist leader in the Communist party in the US in the 1940s and then as a communist activist in Britain after being deported in 1955, she always spoke fearlessly about the women’s struggle.

She really made the connections between race, gender and class – she was intersectional before that was really understood as a term. She was in a party dominated by men, and she was front and centre arguing about the need not only for working-class representation, but also for women’s inclusion and for people of colour.

The other thing that resonates is that she was born in the Caribbean and then went to the US before coming to Britain, and so her life represents the African diaspora. She arrived in Britain at the height of Windrush racism in the mid-50s and fought to oppose the restrictions on Commonwealth citizens coming to Britain. The fact that Commonwealth people who have spent most of their lives in Britain are still being deported today, as in the Windrush scandal, is something that she would have been disgusted by. Hers is a legacy we must remember and continue to emulate.

Valerie Amos is the director of Soas University of London

George Washington Carver by Jak Beula

George Washington Carver was an inventor and agricultural scientist whose work in the early 20th century ultimately gave us peanut butter as well as 300 other products derived from peanuts, including soaps, flour and insulation. He gave it all away, dedicating his patents to the American people.

He is no different to other achievers of African American descent who have not been given their due space and place in history. I was contacted in 2004 by English Heritage; it had only 15 plaques to people of colour in England. That is why we started the blue plaque campaign to have people of black descent recognised. In the years since, we have put up more than 50, as well as two statues – one of which is a memorial in Windrush Square in Brixton to the African-Caribbean soldiers who fought in the first and second world wars.

When you memorialise historic locations, and people such as Carver, you celebrate our common heritage. People should be more aware of who we live among and our shared histories.

Jak Beula is the founder of the Nubian Jak Community Trust

Alice Kinloch by Hakim Adi

Alice Kinloch was a South African activist who came to Britain in the late 1890s and helped to found the African Association, although that is usually credited to a man, Henry Sylvester-Williams. The African Association convened the First Pan-African Conference, which was held in London in 1900. This was the first major event to use the term pan-African and to gather people from all over the diaspora to speak with one voice.

Kinloch has been written out of history, and not much is known about her – I have never even seen a picture of her – but she played a leading role at a time when few African women were active in politics in Britain or elsewhere.

Hakim Adi is a professor of the history of Africa and the African diaspora at the University of Chichester

George William Gordon by Priyamvada Gopal

George William Gordon was hanged after the Morant Bay rebellion of 1865, when hundreds of Jamaicans protested against the abject poverty of colonial rule. A mixed-race Jamaican and a British subject, Gordon was accused of having planned the rebellion, although his only “crime” was to speak out against planter rule and colonial misgovernance.

His swift hanging caused a huge controversy in Britain. He became a martyr around whom there emerged the first rumblings of solidarity across race lines. There were working-class meetings around the country to commemorate his death and to organise protests. People even held mock funerals for him and argued that although he was a different colour, he was still an Englishman, and that anyone could become a target of the empire.

Priyamvada Gopal is a reader in Anglophone and related literature at the University of Cambridge

America faces an epic choice...

... in the coming year, and the results will define the country for a generation. These are perilous times. Over the last three years, much of what the Guardian holds dear has been threatened – democracy, civility, truth. This US administration is establishing new norms of behaviour. Anger and cruelty disfigure public discourse and lying is commonplace. Truth is being chased away. But with your help we can continue to put it center stage.

Rampant disinformation, partisan news sources and social media's tsunami of fake news is no basis on which to inform the American public in 2020. The need for a robust, independent press has never been greater, and with your support we can continue to provide fact-based reporting that offers public scrutiny and oversight. Our journalism is free and open for all, but it's made possible thanks to the support we receive from readers like you across America in all 50 states.

On the occasion of its 100th birthday in 1921 the editor of the Guardian said, "Perhaps the chief virtue of a newspaper is its independence. It should have a soul of its own." That is more true than ever. Freed from the influence of an owner or shareholders, the Guardian's editorial independence is our unique driving force and guiding principle.

Comments

Post a Comment